3OS Paper #4

Abstract: The realities of political pressures shape employment more than enemy capabilities, yet both must be balanced to maintain readiness. Equipping the modern US military that can be both a strategic deterrent but also a tactical victor without succumbing to fiscal pressures and suffering a strategic loss due to second order effects of myopic acquisition policies is a difficulty the entire US Department of Defense (DoD) is failing at. To be a more effective fighting force that can win in any environment without succumbing to financial ruin will take changes in doctrine and policy within the DoD, especially when history shows us that the political pressures in Washington, D.C. are unlikely to change in any administration.

Reinventing the Calculus

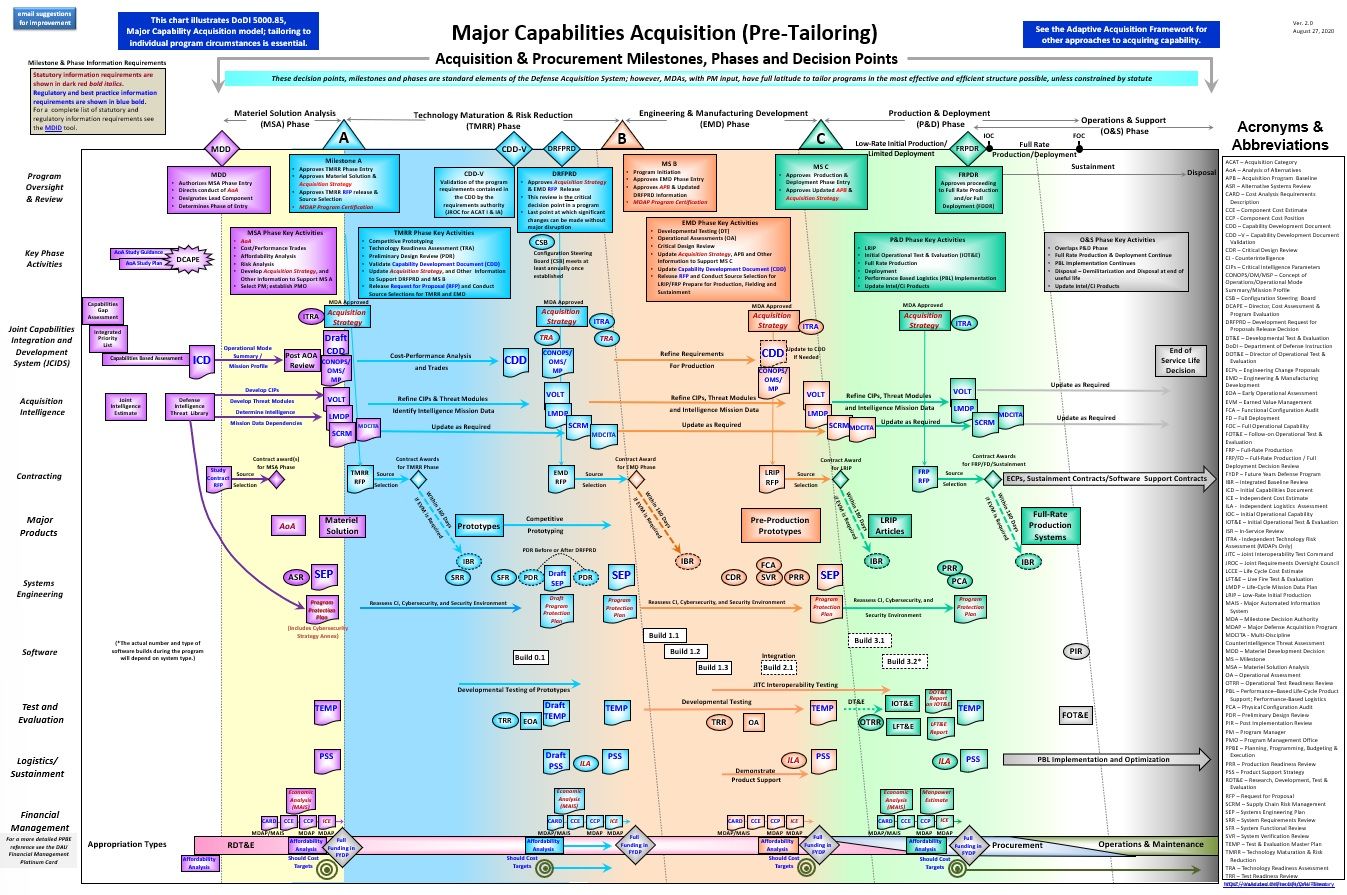

Unlike Mary Tai's errant "rediscovery" of the trapezoidal rule in her 1994 paper,[1] the term "reinventing the calculus" is used here to describe the need for the US DoD to recalculate strategies relative to the future without losing sight of lessons learned from the past. As a matter of policy, the US DoD tries to do both things to their extremes all too often; individual services like the US Air Force (USAF) will create new weapons systems for fighting in familiar ways - dogfighting in air-to-air combat for instance - in ways never thought of before. Truly cosmic forward thinking. Conversely, the entire defense acquisition system - as eluded to in much more detail in the previous paper in this series - is built around refighting the last war 3-5% more efficiently.

All of this fails the reality test. The US DoD wastes more money doing dumb things than any other bureaucracy in the world.[2] For the level invested, the US DoD is the world's most advanced maneuver warfare force in the history of the planet. Yet that may be a dead (or at least dying) way to fight a war. As was noted in the second paper in this series, our near peers have already figured out their own pivots to neutralize many of our advantages, and our foes in the trans-national criminal organization (TCO) space have already figured out ways to vastly outperform the US DoD on a dollars/effectiveness ratio, making protracted counter insurgency (COIN) operations for the US DoD a major strategic threat to American defense capacity and readiness.[3]

The point of the first paper of this series must be explored in a bit more depth: the dire need for an offset pivot that takes advantage of the US economy's strengths and can exploit the economic weaknesses in how rival nations are constructed. Just as our enemies consider the tenets of freedom of speech a weakness they can use to exploit us, we need to consider their kleptocratic, scarcity based or outsourced manufacturing based economic systems a weakness we can exploit at the strategic level. To do so will take new tactics.

Circling back around to lessons learned from World War II seems to be a running theme in these papers; in the spirit of that, the image above depicts a fictional comparison of two very different apexes of technology. In the superimposed photo - of an F-22 Raptor, the USAF's premiere fifth generation fighter jet, and the Imperial Japanese Navy battleship Yamato - the point is not to highlight their massive differences in technology, but their shared technical, tactical and perceived operational advantages relative to the designed warfare they were expected to face. Because of that, the F-22 is likely to find itself in all the same numbers of air-to-air dogfights as the number of broadsides the Yamato found itself in: a number extremely close to zero.[4] This is no accident: they either had a real or perceived superiority over the rivals in the same tactical space forcing the enemy to adapt tactics and pivot away. For Nimitz, Halsey and the rest of the Pacific fleet, the Yamato was hunted mercilessly by aircraft, effectively nullifying its battleship capabilities and removing it from the fight it was designed to win. For the F-22, no sane actor would throw aircraft into the sky in an attempt to dogfight against it; even its non-classified tactics and weapons capabilities make it the most dominant air fighter ever constructed; reality is its even more lethal than the public understands. Because of that, the idea of fighter-to-fighter conflict is effectively a different calculus in understanding joint operations.

The title of the paper is an intentional thought experiment on multiple nuanced layers for a reason. On first glance, an emotional reaction to the question of what is more dangerous, a nuclear weapon or a peanut butter sandwich, is no contest: the most powerful weapon of war ever devised is definitely the most dangerous, right? Except reality says, nuclear weapons are buried pretty deep in Pandora's Box. The last one used in anger was on August 9th, 1945,[5] and since Soviet nuclear parity in 1978 and the US employment policy of 1980,[6] mutually assured destruction (MAD) has prevented use of nuclear weapons in a global exchange. Basically everyone knows if you use a weapon of mass destruction (WMD) against the US (or Russia for that matter), the response will be cataclysmic.

What's so dangerous about a peanut butter sandwich? Peanut allergies have killed many Americans, and the rise since 1990 has been described as an epidemic.[7] So, strictly on numbers alone, since the end of World War II, the peanut butter sandwich is in fact more deadly than a nuclear weapon.

The reason for the nuance in the title though is that even that secondary conclusion lacks context. Are peanut allergies so prevalent that schools and daycare centers should ban the humble legume? Is it truly an epidemic?[8] Most likely not. You're still more likely to be struck by lightning than die from a peanut allergy.

The inspiration for such a dynamic comparison between a child's sandwich and a WMD was taken from a book that forced the reader to re-examine things that might seem like common sense, but are in reality, far from it without a lot of context.[9] It's this type of attention to contextual detail that most policies in the US DoD lack at the doctrinal or acquisition level, which is shocking as from the strategic levels down to skirmish level, the US DoD is brilliant at contextualizing threats and tactics. This inability to modernize is somewhat political, but it can be fixed. However, before it can be fixed, it has to be acknowledged.

The contested myth

USAF leadership has woven a tale of difficult choices when choosing to divest itself of the A-10C throughout the mid-2010s.[10] Some statements were based on well-intentioned naïveté, such as Scott Wolff's paper in 2019,[11] while other acts by USAF leadership were full-blown legal violations.[12]

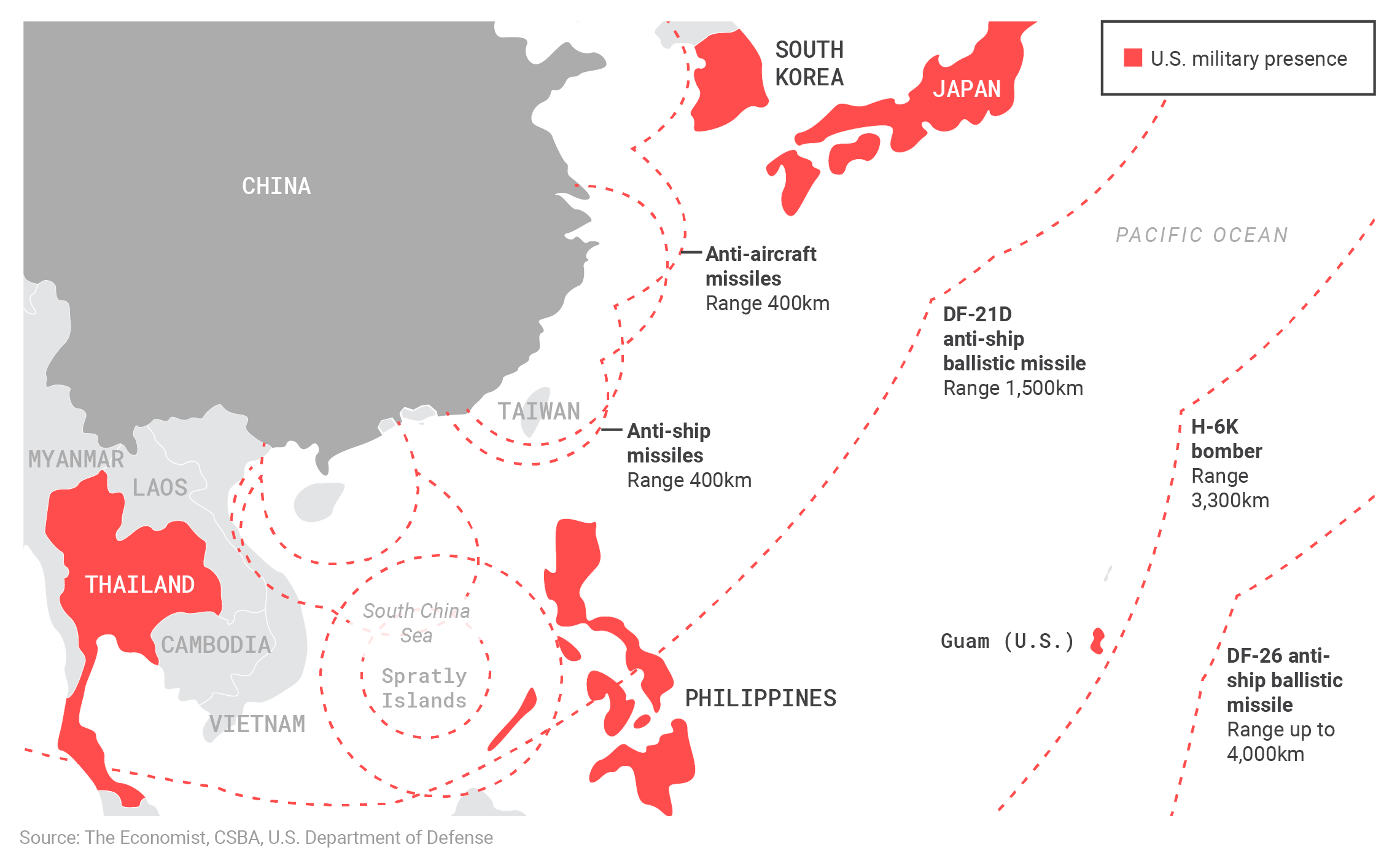

The tale told by USAF leadership was that costs borne of need for fighting through Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) threats in Contested/Degraded Operations (CDO) as part of Major Combat Operations (MCO), the US DoD in general, and the USAF more specifically were going to need fifth generation platforms such as the F-22, F-35, B-2, the upcoming B-21 and possibly even un-retired F-117s for penetrating deep into areas protected by double-digit surface to air missiles (SAMs). And for this specific type of engagement, not only is the A-10C a worthless piece of ancient iron, so are most of the USAF's (as well as the US Navy (USN) and US Marine Corps (USMC)) tactical aircraft. The various versions of F-15s, F-16s, and F/A-18s are all mere targets for these advanced SAM systems.

The A-10C conversely, is vastly superior to not merely its fellow 3rd and 4th generation F-15, F-16 & F/A-18 counterparts in the roles of close air support (CAS) and personnel recovery (PR) support/escort, it is truly superior for these roles to the fifth generation platforms that the USAF considers the future.

The sound of freedom being sprayed at an enemy rather rapidly with a "full liberty" level of force.

This is isn't a controversial statement by anyone, and has been gospel since the days when the Air Force eschewed multi-role fighters. The attempts by USAF to find a new way to live up to the Key West Agreement[13] is fraught with issues, both acknowledged by the Air Force, and also often denied when reality was hard to deal with.[14]

Air Force leadership has had to make hard decisions about the future of the combat forces and their ability to service all the types of targets and needs that will be required - from the Army's needs for CAS up through the core needs for deep strike, air superiority (or, more favorably, air dominance). To succeed in all of these roles, and have enough money to pay the Airmen and support their families, something was going to have to give. With the budgetary guidance from not only the US DoD but Congress, the prudent decision is to divest from single-role aircraft to multi-role aircraft and consolidate services in an effort to save money.

Of course, this doesn't necessarily fit with budgetary reality either.

Senior Air Force officials are quick to justify that you can kill the A-10C because it can't survive in an anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) fight, and the F-35 is "capable" of conducting those missions.[15] If the F-35 is capable of effective CAS is wholly debatable unto itself. That it's anywhere near as good as the A-10 isn't.

At $42,000 cost per flight hour (CPFH),[16] the F-35 shouldn't fly in support of low-intensity conflict (LIC). Pilots should do the vast majority of their stick time in simulators, and the aircraft shouldn't be used at all except in the rarest of circumstances. The massive number of them purchased is an abject waste compared to the mission sets they are needed for and the cost to operate them.

Of course, the F-35 wasn't just a Cold War acquisition decision based on assumptions about air combat that don't correlate to modern reality, its additional brilliance was in getting parts for it made in 307 (out of 435) Congressional districts across 45 states.[17]

The oft touted figure of $3.7b in savings had USAF divested itself of the A-10C when they proposed such in 2013[18] was smoke and mirrors; for almost the entirety of the half-decade that the Air Force proposed those savings would occur, the A-10C continued to fly in Afghanistan and Iraq/Syria against the Taliban, al-Qaeda and ISIS, enjoying not only a supremely favorable record of employment as a ground attack platform, but dominating in the cost comparisons.

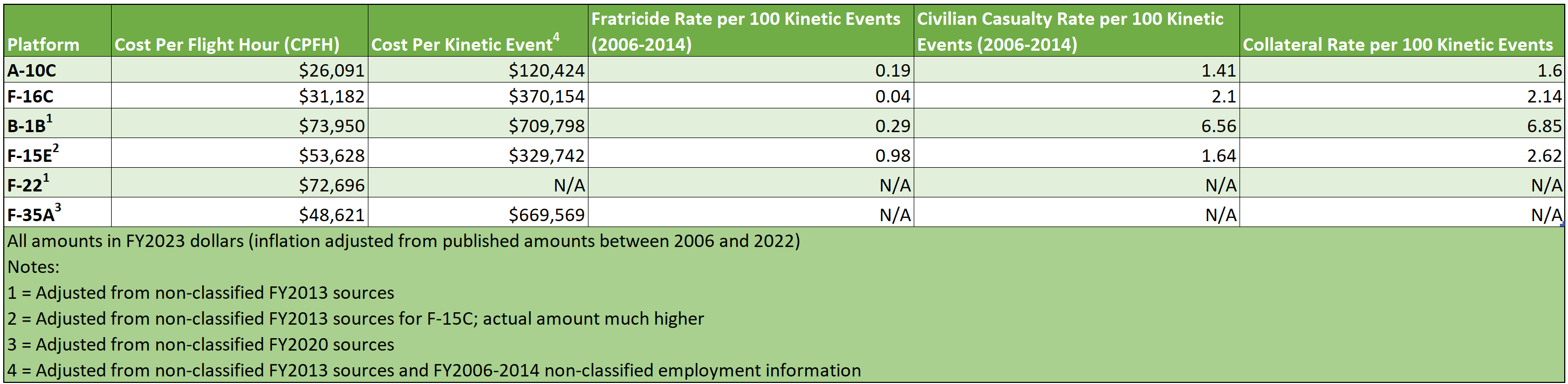

Based on the average number of kinetic sorties flown between 2010-2014 available from public sources,[19] if the costs were extrapolated to compare both the cost per flight hour and cost per kinetic engagement from the A-10C to the F-35A, USAF would have paid an extra $4.2b over the same five year period they would have supposedly saved $3.7b for a net loss of $500m to achieve the exact same number of flight hours and kinetic engagements. Ergo, the argument about cutting the A-10C to replace it with the F-35A would save money is only if the Air Force is willing to tell the Army that they can't get as much service for CAS. With regards to the secondary mission of the A-10C, PR support/escort, there is no other platform that can fly in the rescue helicopter's threat envelope. In spite of this risk, the F-35A would theoretically be a capable PR support/escort platform given its visibility advantages in CDO situations, even if it won't be in the same threat envelope as the rescue helicopter; mere adoption of new tactics, techniques & procedures (TTP) would allow for this projected gap to be filled.

The US DoD drastically changed their department-wide focus from counter insurgencies (COIN) and counter terrorism (CT) to MCOs with pacing threats with the publication of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS). This has been necessary for quite some time; as was pointed out in the second paper in this series, Russia and China have been able to develop their offset strategy pivots for decades to rapidly close the gap with US hegemony and nullify many of the US DoD's advantages, albeit Russia has then squandered their pivot advantages in Ukraine.

USAF leadership would have been more well received had they used this vital realignment of priorities from the US DoD as justification to kill the A-10C than the misleading argument of "cost-savings" which was arguably wrong anyway depending upon how figures were calculated. When talking about the context of cost savings, what is vital is understanding probabilities that go into calculations, and in this context, there is no argument: platforms like the A-10C and other 3rd and 4th generation platforms will have plenty of opportunity to be employed if past history is any guidance.

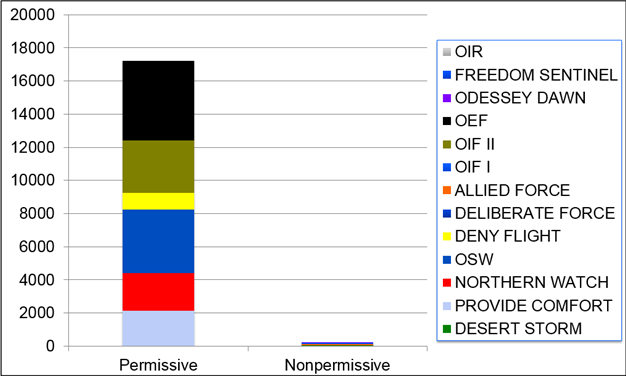

From Col Michael "Starbaby" Pietrucha's excellent piece on actual high-threat CAS,[20] the comparison of use of tactical aircraft for combat operations is a massive disparity. To be fair, for the column on the left (permissive), if any of those colors are in the column on the right (nonpermissive), the left column's data can only exist if the right column does first; you can't effectively create a permissive environment without eliminating the enemy assets that create a nonpermissive environment. For some of these, like the gigantic black block for Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) which the majority of operations in Afghanistan fell under, the "nonpermissive" environment didn't require a 4th generation platform to even fly advanced tactics; the B-52H was perfectly capable of flying into Afghanistan on day one and creating a permissive environment after the handful of archaic SAMs and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) were destroyed.

Of course this isn't to be expected in an MCO with a near-peer; air dominance will be unlikely and air superiority and CAS in a permissive environment difficult to achieve.

This begs the question though: what is probable?

The last time USAF did high-threat CAS in support of conventional, non-special operations forces (SOF), it is highly unlikely any current USAF Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTACs) or CAS pilots were even born. There exists doctrine within training for high-threat CAS,[21] and most JTACs and CAS pilots train for such an event. Just because it is doctrine and trained for however, doesn't mean the conditions to do such a thing will occur, and this isn't just due to TTP, but rather due to politics.

Conditions leading to high-threat conventional CAS aren't just hard to imagine for CAS professionals, they are hard to imagine for just about everyone. When the USAF began development of the Guided Bomb Unit (GBU) 53, also known as the small diameter bomb (SDB)-II, the concept of operations (CONOP) vignette developed for JTAC controlled CAS as envisioned by the weapon developers for "common usage" actually represented an extremely fringe use-case that only a tiny minority of SOF JTACs would ever do, and most likely no conventional JTACs ever would.

This type of misunderstanding is far more troublesome when people start to think about strategic and operational level problems without the context of strategic issues or other national security instruments such as diplomatic, informational, military and economic (DIME) influences. Examples of this include thinking about "the million man swim" across the Formosa Strait and the issues the 7th Fleet would have or the Kaliningrad S-400 and Iskander missiles relative to North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies in the Baltics and Eastern Europe without taking into account the other economic and diplomatic ramifications of wars with China or Russia, respectively.

Of course, that doesn't mean a previously rational actor may believe an irrational provocation will result in a tangible goal without the consequences that a rational actor may otherwise expect. As mentioned in the first paper in this series, Pearl Harbor on 7-Dec-1941 was not merely irrational from the perspective of modern-day historians (Admiral Yamamoto would have served Imperial Japanese and Nazi German aims far more effectively by bombing Vladivostok in the winter of 1941/42 given the Russian movement of forces to counter-attack Operation Barbarossa; forestalling the American entanglement into World War II and encircling Soviet forces would have done the Axis far more good than to entangle the US into a large-scale war while allowing Soviet forces to regroup effectively), it was irrational to Japanese strategists - to quote Yamamoto, all Pearl Harbor did was "awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with resolve."

A Russian or Chinese actor may suddenly - errantly - push things too far in an attempt to escalate-to-deescalate and create a genuine catastrophic war situation. However, this is the reason the "leviathan" force[22] to deter or destroy enemies in an MCO exists. Its mere existence however shouldn't be the basis of all fiscal decisions by the US DoD as it presents a completely different risk, where small non-state actors can bleed the coffers of the taxpayers completely dry by asymmetrically exploiting a spending advantage.

To prevent this is easy: what is the most common type of employment of American force, and how can we lower that cost threshold to make "war" less costly when its palatable to the US public, and therefore, likely to be approved by Congress and the Executive?

A simple glance through historic use of US forces finds very few skirmishes against near-peers. The US revolution, the War of 1812, the Civil War, Spanish-American War, World Wars 1 & 2, and the Korean War. Seven wars in 245 years where loss could catastrophically change the calculus of the US's relationship to itself and the rest of the world. The other 300+ deployments of US troops to foreign lands has been, while often very destabilizing to the foreign nations of interest, were of minor political threat to the US government. Examples of this in recent memory are the bombings of Serbians in Kosovo, the continued CT operations in Africa and Central Asia occurring even now in 2023, the actions in Somalia in 1992-93 and again from 2017-present, the capture of Manuel Noreiga and the invasion of Panama in 1989, the firing of cruise missiles into Sudan to hunt al-Qaeda leadership in 1998, etc. These are typical employments of US forces as the reasons are often politically popular while having very little political risk for Congress and the President.

This reinforces Col Pietrucha's point about permissive vs. nonpermissive employment of forces. When the Air Force pitched the retirement of the A-10 in 2013, between operations in Syria and Afghanistan, it would be eight years after this initial pitch where the A-10C would continue to be the most cost-effective and mission-effective asset in the entire USAF inventory. Theoretic cost savings would have actually been major overruns and reductions in both mission accomplishment in the deployed theater and less capacity for deterrence of an MCO with a near-peer.

In spite of all of this however, "saving the A-10" really isn't a good idea nor cost-effective in the long run.

In a USAF built around "large iron" - which is to say large, manned tactical aircraft operating in the battlefield, then, yes, the A-10C is among the most cost-effective and tactically effective assets in the inventory. However, the idea of "large iron" or even manned tactical aircraft is dated thinking. Given a leadership model that rewards consistency and risk aversion, and an acquisition model that is designed around small methodical incremental advancement, it is no shock that the types of tactics and acquisitions from Vietnam through Desert Storm are the basis of decisions within the Pentagon. This paradigm must be shattered. The warfighter must take the lead by demanding new TTP and new operational and tactical options and modularity. Simply refighting the Cold War with the Fulda Gap moved to the Formosa Strait won't work.

Bring on Skynet

The US DoD has many organizations working on new advancements including Replicator at the Office of Secretary of Defense (OSD) level,[23] including the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA),[24] the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU),[25] the Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO),[26] and then several more inside the USAF such as the Air Force Research Laboratory's (AFRL's) "Skyborg,"[27] as well as numerous other projects within AFWERX.[28] Most of these pertain to small unmanned aerial systems (sUAS), but all of them are in areas of defense acquisition often referred to as "the frozen middle."

This is unfortunate, as the "real money" - and most likely the real acquisition dollars allocated to program elements (PEs) and executed by the system program offices (SPOs) are going towards new air dominance fighters[29] that will probably be mostly wasted budget in terms of actual use.[30]

For contractors like Boeing or Lockheed, second guessing the requirements process of the Air Force isn't their job; maximizing profits and shareholder value is and should be their goal.

With the idea of tactical fighters engaged in a multi-role fight, the idea of the "century series" manned platforms that evolve rapidly with newer capabilities while also having a "shorter" shelf-life than the expensive to maintain geriatric USAF of today are all definitely tactical advantages over the existing systems from a warfighting perspective. From a strategic perspective, they seem further advantageous in the pressure they put on a near-peer to fight according to our calculus; however, the relative cost we incur relative to not merely a near-peer, but to their lower-cost proxy forces may in fact be a huge strategic step backwards. From an operational perspective in context to likely enemy, they will be a colossal waste of money, effort and capability.

The modern fifth generation platforms can already "outfly" the human inside, just as the fourth generation platforms before them. This was the entire basis of discarding the argument of the F-35 potentially being less maneuverable than the F-16 it was going to replace; the pilot's consciousness threshold is the actual barrier, not the jet's level of alpha.

Col Randy "Laz" Gordon, PhD, an F-22 test pilot has an amazing YouTube video about the F-22's flight controls he gave at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (his alma mater) in 2019. During the questions and answers with the flying club in attendance, he noted that the aircraft was vastly more capable in terms of physics than the pilot inside. Luckily we have software to save pilots[31] during training that can prevent catastrophes. But what if the pilot is the catastrophe? In a tactical dogfight, the human physiological capability is already a drawback; when does the mental advantage of the human erode all tactical superiority?

Col Gordon's lecture also tackled that question about artificial intelligence (AI), and how AI was unable to defeat a human pilot. But that was 2019, and in the era of technology, a lifetime ago. Col Gordon would actually help stand-up the AI pipeline between MIT and USAF during his assignment in 2019-2020. Another US DoD AI project, this one at DARPA has already shown the human's cognitive abilities are now behind the machine in a dogfight.[32] The human is already a physical "flaw" in the fourth and fifth generation fighters and their basic maneuvering. They are now a cognitive weakness, as the AI has superior observe-orient-decide-act (OODA) loop processing capabilities and holistic fighter-maneuver knowledge.

For computer nerds, this evolution has been a long time coming. When the world's greatest chess master was defeated by AI in 1996, it signaled the changing of an era, but for over 15 years now computer AI has regularly toppled even the most skilled human opponents.[33] The fighter pilot would like to think of their craft as more complex than chess given the myriad factors involved, from complex aeronautics and four dimensional physics to weapons systems capabilities, but these are all reducible calculations a computer can consistently "solve" better than a human brain. So for a future air dominance platform, we're already wasting money designing a system with a cockpit for a flawed bag of water with limited cognitive function to sit and waste valuable clock-cycles of decision superiority and physiological superiority that the AI would have.

The sixth generation tactical air dominance platform should be wholly AI with no human in the aircraft. Yet the investment in such a platform should be akin to the type of investment in the F-22 - minimized to what is necessary to gain air dominance against a near-peer. Because as a platform for the majority of engagements that Congress and the Executive will be comfortable sending the US DoD on an expedition, AI will be key in the air platforms above, but they certainly won't be expensive low-visibility long-range high-performance aircraft. They'll be swarms of modified commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) platforms.

Congress picks the place and time

While it is convenient to blame Congress (or the Executive) alone for decisions to deploy (or not) for the military, the politics are also within the US DoD itself, not merely because of risk to career officers over mistakes in strategic-level planning, but due to the design of command relationships in the post-Goldwater/Nichols reorganization. Understanding the roles of how the joint force structure is laid down, and how the relationships between the deployed services are much "blurrier" in the forward theaters under the umbrella of a unified combatant command (UCC), this further skews the actual demand for perceived assets by the service-level requirements generators (in the USAF, this would be either headquarters, Air Force (HAF) or Major Command (MAJCOM) level A-5 staffs) compared to the deployed commander's needs. The entire relationship is so fundamentally flawed a secondary acquisition path had to be developed during the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) called the urgent operational needs (UON) process (and its joint cousin, the JUON). The fact that the existing requirements process as part of the greater capabilities development process was flawed has only tangentially been explored by the US DoD in general.

The US DoD acquisition process is more heavily indicted in the previous post in this series, but it is worth revisiting if for no other reason than to show that there is disparity between how the services equip themselves and how warfighters actually go and fight. In both cases, Congress and lobbyists have far more sway than military leaders.

When it comes to actual employment - and why we spend so much more time needing low-cost platforms to do missions like CAS for years on end instead of the relative few days every couple of decades to do intense air-to-air and nonpermissive establishment of air dominance, the political constraints put on UCC leadership is the primary factor.

There is no appetite in Washington D.C. for anyone to be associated with deploying troops into harm's way and then them coming home as neatly folded flags. No Congressmen or President wants to be associated with a "loss" by our Defense Department if for no other reason than damage to their re-election campaign or impact on their political party's standing in the next elections. This is why the Joint Force Commander (JFC) of any given UCC has numerous constraints from getting troops unnecessarily killed, and a perfect example of that is the deployment of conventional forces under enemy aircraft; this hasn't occurred at all since Vietnam, and really, with any threat since the 1950s in Korea. In both invasions of Iraq - in 1991 and 2003 - the JFC did not give the Joint Forces Land Component Commander (JFLCC) - usually the senior commander of all deployed US Army (USA) forces in that UCC - permission to move conventional forces into harm's way until after the Joint Forces Air Component Commander (JFACC) - usually the senior commander of all deployed USAF forces in that UCC - had successfully neutralized all of the air threats. In practice, USAF achieves complete air dominance prior to the JFLCC's order for conventional USA forces to move into harm's way, and does so with a very favorable CAS conditions.

In this typical employment paradigm, the need for fifth or sixth generation platforms exists, but temporally, it's a tiny minority of the time where USAF needs to provide combat aircraft to have battlefield effectiveness. The use of lower cost platforms such as the A-10C, A-29, AT-6 and other light attack aircraft would all be massive savings given the engagement envelopes the ground forces will be deployed into.[34] CAS aircrews and their corresponding JTACs on the ground can and should continue to train for high-threat CAS in an MCO with a near-peer including continuous CDO such as high-density A2/AD threats, but the reality of history and politics is that CAS assets will be taxed for long time frames in support of conventional forces only after air dominance is achieved, and that this time frame can in fact be so long that the sustained cost to maintain CAS capabilities for the JFLCC's ground assets will present the USAF with a detrimental cost burden that may pose a strategic risk to the US's military capabilities and capacity.

The only circumstance under which a JFLCC's ground assets will request CAS from the JFACC's air support platforms under contested skies will be during a surprise attack by an irrational actor. The casualties will be catastrophic in the first phase; most USAF JTACs would immediately think of South Korea being invaded by the North, and they know the result as well; most multi-role USAF aircraft will be focused on achieving air dominance and while ground commanders will be lucky to receive any CAS support, they'll be luckier yet if those USAF assets can prevent the enemy's use of effective CAS against our ground forces. No JFC's career, much less those in Congress or the White House could survive the political fallout of dead Americans killed en masse by enemy air support.

Thus, the entire argument of contested CAS is about a real thing that may really happen, but in ALL circumstances is a niche use case that lasts for an extremely short time-frame, and thus, long-term fiscal responsibility would be best served by having a mix of low-cost platforms that can sustain capacity for deployments with CAS servicing for longer time periods.

Reimagining national defense strategy

The same USAF Major General who made the mistake of suggesting Airmen talking to Congress about aircraft capabilities were committing treason also famously said "I can’t wait to be relieved of the burdens of close air support."[35] This would be in gross violation of the Key West Agreement,[36] but really the entire US DoD doctrine for CAS - whether contested or not - needs to be drastically changed along with many other facets of joint doctrine in an effect to modernize the process of warfighting. The Air Force's dual efforts[37] on February 10th, 2020[38] to basically "get out of the CAS business" were myopic, misguided, poorly constructed and based on the same naïve thinking that A-10s costs were going to be recovered by use of the F-35. But should the Air Force still be in the CAS business the way its organized and designed now? Probably not. Because national defense needs to be rethought on multiple levels.

The last paper dealt with our inability to integrate the advantages of the commercial space with our acquisition strategy and why our enemies - from near peers to TCOs are able to operationalize American technology better than the US DoD. The next paper will get into our inability to properly operationalize the "multi-domain" battle space, and why our historic roots in intelligence-community governed cyberspace operations has moved us behind in cyber. But none of that matters without acknowledging the elephant in the room: the way the US DoD is organized is a huge problem with modernizing warfighting. And the entire point of this paper has been to characterize the existing US DoD - and more specifically USAF modernization - policy has been based on errant guidance. It is going to take a major change in how senior Defense leadership view these bureaucratic problems to solve these issues.

The US DoD needs to change their focus at all levels of warfare, from strategic through skirmish, to refocus on realistic readiness for real warfare, and adapt both acquisitions and TTP for far faster knowledge velocity, with our operators and enablers all operating in an OODA loop far faster than our opponents in the types of warfare they are willing to fight in - hybrid warfare, cyber warfare, counter-proliferation, or use of low-cost TCOs as a proxy to attrit US DoD capacity.

Sadly, there's a reluctance to change when deeply entrenched bureaucrats are married to a system that has made many lobbyists (and lawmakers) filthy rich, while a massive wave of unionized employees within the US DoD tied to legacy processes still pushes back against innovation. The railroading of Michael Brown's nomination as Undersecretary of Defense (USD) was a classic example of this entrenched system creating threats to national security.[39]

"Make no mistake, Brown would have shaken up the system, and the losers would have been the Chinese, the traditional defense contractors, and public employees who don’t want to change to meet the threats of our times." Bill Greenwalt, author of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) 2016 §815 that expanded Other Transactional Agreement (OTA) authorities NDAA 2016 §804 for middle-tier acquisition.[40]

The US DoD as an enterprise is woefully unprepared for most of these because its still organized around an architecture built around Cold War acquisitions and counter terrorism operations, neither of which support real future wars.

Every Airman is a (sUAS) Pilot

With the rise of Fractal Airpower as a tenet of combat, the scope of who can be a functional component of the JFACC's presentation of theater forces for airpower has grown wildly. After all, the reality in Ukraine is that hacked-together explosives on a first-person view (FPV) piloted sUAS has grossly increased effective airpower in use against Russian forces.

This expands on the operationalized culture theory beyond just shared values, but into shared ceremonies; something one of the other services - the US Marine Corps (USMC) has nailed. In the Corps, "Every Marine is a rifleman." It's almost a meme.

Nonetheless, there is an ethos in the USMC about their role and their responsibilities. Nothing of the sort exists in not merely the USAF, but the Army or Navy either. By creating a culture within the USAF where everyone can possess training, and then ultimately, the talent to be part of the generation of actual airpower plays a role in both the greater value of Fractal Airpower, but also the values and rituals within the USAF as a military service itself.

To instill this culture, or rather, the "family business" as has been referred to by the architect of the program within the USAF, training of FPV-piloted sUAS, as well as the basics of building/equipping them must be part of the USAF educational model across the entire enterprise. The program, currently termed "Airpower For All," seeks to change USAF understanding of airpower on a fundamental level, while also create an infrastructure that will allow for rapid development of TTP.

The creation of an Air Force-wide training program aligned with professional military education (PME), will allow the USAF to instill tenets of airpower into the entire force structure. By ensuring every airman understands the tenets of Fractal Airpower, they become part of the joint firepower capability the JFACC can offer the JFC, but also makes each airman an empowered member of the greater USAF, prepared to execute on the edge instead of just merely being a force-power generator on behalf of a small cadre of pilots.

From an enterprise perspective, this also creates a more comprehensive framework for Fractal Airpower to be part of both a distributed edge-based model of FPV-piloted sUAS, but also allows for autonomous sUAS and various different platform sizes to integrate into broader networked systems such as Air Force Special Operations Command's (AFSOC's) Adaptive Airborne Enterprise (A2E)[41] and DoD's Replicator.

Algorithmic Dogfighting and the Rise of the Software OODA Loop

Programs like Airpower For All, Replicator and A2E are all innovative mergers of adopting new acquisitions policies with rapidly developing TTP. Policies like the Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO), expanded use of small business innovation and research (SBIR) funds, and use of blended commercial and continuously auditing and validating security posture on post-container build systems acquired from the commercial sector all play pivotal roles from an acquisitions perspective. Additionally, internal software development that can be delivered through a continuous integration/continuous delivery (CI/CD) pipeline can combine with those acquisitions and rapid iterative development of TTP that feed into the software development lifecycle. Using agile development principles as close to the tactical edge as possible - embedding software designers at the squadron level with access to deployment tools on a continuous authority to operate (cATO) won't just create a remarkable advantage *RIGHT NOW* but will also create a platform for continously improving TTP.

The future of combat will include much more autonomy and robotization than currently employed, and will be built atop layers of different types of AI and machine learning (ML). Those layers of technology will then work in conjunction with human operators that rapidly process complex information in easy to understand methods. This will then enable faster pathways to lethality.

As a thought experiment, imagine contracting an innovative small business to adapt gaming technology like Unreal Engine to create virtual training grounds for FPV-piloted sUAS, with two goals. The first would be to allow combat operators, such as those on the front lines in Air Force Special Warfare (AFSPECWAR) to train on a target location built in a simulator over and over again prior to real-world mission execution, both to train the operator on what they'll be expected to see, and also to use reinforcement learning techniques to teach the AI algorithms on the mission sUAS to further assist in operations. The resulting combat employment would feature a well prepared human and a well prepared robot, both much more lethal than current systems. The second advantage would be to create complex but standardized models and allow airmen to compete against each other across the entirety of the USAF, creating a massive cadre of combat capable airmen who can deliver effects as part of a Fractal Airpower construct.

Even more importantly, larger-scale combat operations of wholly autonomous aircraft - mostly built atop the same low-cost dual-use hardware as the FPV-piloted sUAS and using the same software delivery pipelines - would have a massive quantity of training data to use for algorithmic enhancement. The robots will be better for all the FPV-piloted sUAS, even for combat applications where the tyranny of distance and the necessity of massive swarms would prevent FPV-piloting from being workable altogether.

The coming wars we must be prepared for will range across the spectrum from special operations (SO) / LIC to MCO inside an A2/AD bubble forcing difficult CDO. For the SO/LIC situations, time on ground could range from hours to months, but the current Cold War model is far too expensive in all cases, and new capacity combined with new TTP will be required to keep from breaking the "leviathan force" that can prevent an MCO by just its mere existence. In those situations where an MCO does become reality, the existing time phased force deployment data (TPFDD) war plans are probably obvious, both because we widely publicize parts of them, such as the agile combat employment (ACE) operational imperative (OI),[42] or because it's just the same thing we've always done with long-range force projection. Fighting that way will probably be a fight the US DoD will win, as per publicized results of wargames,[43] but at immense cost. By creating new ways to employ Fractal Airpower, and associated technologies through programs like Replicator using innovative software, we force the enemy to completely rethink their entire force projection calculus.

This pivot would allow us to take advantage of the two things the US has in spades: an economy based on knowledge and software, and chaotic military operators willing to rapidly pivot TTP in the battlefield. That type of transition will make the US far more unbeatable than just a new tactical fighter.

This type of strategic pivot wouldn't merely impose new difficulties on the enemy, it would create an ever constricting OODA loop of both tactics and acquisition built around what American society and American troops are the best at, thereby keeping a dynamic tactical edge that could last for significant time. As more time goes by, eventually the tenets of a free democracy and open society serve the US very well, while total fertility rate (TFR) related issues will eventually sap China and Russia of realistic power. By the time the US DoD needs a fourth pivot, our near peers will have had to completely retool their entire society (or we'll need to find new near peers).

Header image courtesy of Adobe Stock images.

References/works cited and assorted footnotes.

2 Hartung, William. 2021. Pentagon Waste Takes Many Forms. May 20.

3 Ware, Jacob. 2021. The United States left Afghanistan to prepare for a ware it will probably never fight. October 28.

and

Felbab-Brown, Vanda. 2021. The US decision to withdraw from Afghanistan is the right one. April 15.

5 Lengel, Ed, PhD. 2020. The Bombing of Nagasaki, August 9, 1945. August 9.

6 Marsh, Rosalind J. 1986. "Soviet Fiction and the Nuclear Debate." Soviet Studies (Taylor & Francis, Ltd.) 38 (2): 248-270. Accessed March 12, 2020.

and

Carter, Jimmy. 1980. "Presidential Directive/NSC-59: Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy." Letter to The Vice President, The Secretary of Defense, The Assistant to the President for National Security & The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Washington, District of Columbia, July 25

7 Platts-Mills, Thomas A.E., MD, PhD, FRS. 2015. The Allergy Epidemics: 1870–2010. July.

10 Abramson, Larry. 2013. Air Force's Beloved 'Warthog' Targeted For Retirement. December 24.

11 Wolff, Scott. 2019. The A-10 Warthog debate: A fate worse than death. August 28.

17 Henry, Elijah. 2019. The F-35 Project Has Been a Disastrous Waste of Money. September 3.

20 Pietrucha, Col Michael. 2016. The Myth of High-Threat Close Air Support. June 30.

22 Barnett, Thomas P. M., PhD. 2005. Let's Rethink America's Military Strategy. February.

24 Reyes, Hercules. 2021. General Atomics Unveils Aircraft-Launched Combat Drone Design. July 30.

26 SOFREP. 2019. Watch: US Military Releases Swarm of Micro-Drones from F/A-18. February 23.

27 Air Force Research Laboratory. 2021. . September 15.

28 Benson, Mark. 2021. Energetic Strike sUAS (ES-sUAS). March 1.

34 Kaaoush, Kamal J. 2016. The Best Aircraft for Close Air Support in the Twenty-First Century. Fall.

35 Smithberger.

36 Matsumura, Gordon, and Steeb.

39 Kaplan, Fred. 2021. The National Security Disaster You Probably Missed Last Week. July 19.

40 Ibid.

42 Tucker, Patrick. 2021. Island-Hopping F-35s Test Pacific Air Forces’ Agility Concept. February 24.